Infectious Diseases Case of the Month Case #26 |

|||

|

A thirty-five year old white male was admitted to the hospital for pleuritic chest pain and fever in the fall of 2009. A lifelong resident of Oregon who had suffered with crohn's disease since childhood, he had become ill with headache, muscle aches, and fever approximately two weeks prior to hospital admission. Approximately a week prior to admission he had also developed pleuritic left sided chest pain for which he sought medical attention. Although he lacked a significant cough, his chest x-ray suggested pneumonia, and he received outpatient therapy with azithromycin with subsequent addition of levofloxacin when chest pain and fevers (to 103o) persisted. His treatment for crohn's disease was with mesalamine and azathioprim. He worked in an office and did not typically engage in outdoor pursuits. He home was in an urban environment in a moderately sized community in the Willamette Valley. Approximately three months prior to his illness he and his family had visited southern California traveling through the Central Valley en route. His wife and two young children had not been recently ill. His wife was foreign born from a region where tuberculosis was of high prevalence, and there was concern about possible past exposures to persons with active turberculosis. He was admitted to the hospital because of failure to improve. At the time of his admission he was described as in no acute distress, with lungs clear to auscultation, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Admission laboratories included WBC 8.4, Hgb 13.1 and normal LFTs. He was begun on broad spectrum antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin, and azathioprim was discontinued. Laboratory investigation included CXR and chest CT scan (at left). Urine legionella antigen, urine pneumococcal antigen, serum cryptocococcal antigen, and influenza rapid tests were negative. Blood cultures and sputum AFB smears were also negative. Largely because of concern about the possibility of tuberculosis, the patient underwent bronchoscopy with LUL bronchoalveolar lavage. The bronchoscopist described slightly erythematous uppper airways without purulence or endobronchial abnormality. The patient appeared to improve on the broad spectrum antibiotic therapy and was discharged on cefdinir after a five day hospitalization. |

||

What was the likely cause of this patient's illness? |

|||

|

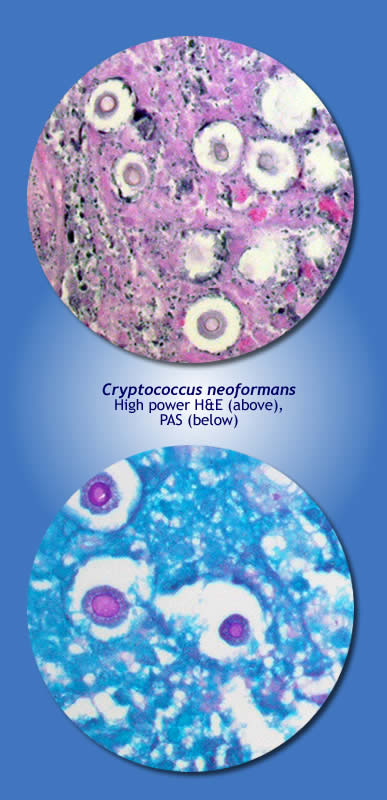

This patient had pulmonary cryptococcal disease secondary to Cryptococcus neoformans. Little in the preceding vignette describing this patient's illness distinguishes the diagnostic choices provided. Growth of fungus identified as Cryptococcus neoformans from his BAL was reported two to three weeks after his hospitalization. He was placed on therapy with fluconazole and evidenced progressive improvement. When this organism was identified as the likely cause of the patient's disease, a lumbar puncture was performed. Results were normal including negative cryptococcal antigen, and there was no subsequent growth of cryptococcus on CSF culture. Pictured at left are H&E and PAS stains of cryptococcal lung disease from a similar patient (the patient in the vignette did not undergo biopsy) showing the encapsulated cryptococcus yeast. In the Pacific Northwest (British Columbia, Washington, Oregon) both Cryptococcus gattii and Cryptococcus neoformans can be found as cause of human disease. Distinguishing these species requires specialized fungal media (concavine-glycine bromothymol blue agar). In this case this specialized identification was performed at the Oregon State Public Health Laboratory. Serum cryptococcal antigen is a fairly sensitive test for disseminated cryptococcal disease, but in HIV negative persons with disease limited to the lungs its sensitivity is only 25-56% perhaps accounting for the negative result here. Cryptococcus gattii has been previously known to cause disease in tropical and subtropical regions of the world (New Zealand, Australia, Southeast Asia, parts of Latin America, Southern Europe). Its emergence as a cause of human disease in North America was recognized in 1999 when a cluster of human cases was identified on Vancouver Island. Its North American ecologic habitat is incompletely defined but may conform to the Coastal Douglas Fir and Coastal Western Hemlock biogeoclimatic zones of the Pacific Northwest. Distinguishing between species of cryptococcus as cause of disease may have clinical implications as there is some evidence that Cryptococcus gattii may be somewhat less susceptible to antifungal therapies than is Cryptococcus neoformans. It is also possible that Cryptococcus gattii may be more apt to cause significant disease in immunocompetent individuals than is Cryptococcus neoformans. Both of these concepts (differences in drug susceptibility, virulence) are the subject of ongoing research. Ref: Data, K., et al, Spread of Cryptococcus gattii into Pacific Northwest region of the United States, Emerg Infect Dis. Aug 2009. |

||

| Home Case of the Month ID Case Archive | Your Comments/Feedback | ||